Barney crosses the James River

As told in Shirt-tail Sunday: Barney Rosenblatt, Part 4 – Barney fights the rebels at Harris Farm, Barney emerged unscathed from the Confederate attack at Harris Farm. He continued to march southward with Company D, 25 miles daily–often through the night–crossing the North Anna River on May 25 and the Pamunkey River at Nelson’s Crossing on May 28. When not marching, wherever they stopped his company built breastworks from mud and branches for protection. James Lockwood recalled:

The army did not pitch tents and make a regular camp for months at a time during this campaign; but simply halted when exhausted, built fires and made coffee or cooked — those did who were fortunate enough to have anything — as the times for eating and sleeping came at doubtful periods in those days, and each man was expected to lie down in place and sleep upon his arms, ready for battle at a moment’s notice.”

After days of marching, some days slogging over rain-soaked ground, Artillery Commander John Tidball decided to make a change. He was unhappy with the performance of his Fifteenth New York Artillery which was assigned a Coehorn mortar battery but spoke no English, only German. On May 30, he placed Company D in charge of their mortar battery instead. Barney and his fellow soldiers in Company D were being rewarded for their bravery during the Battle at Harris Farm by being entrusted with a battery of Coehorn mortars. Coehorn mortars were portable, the smallest of all mortars but effective. The Coehorn mortar with its wooden bed weighed close to 300 pounds but could be lifted by a four man crew. A 24-pound coehorn could land it’s 17-pound shells from 25 to 1200 yards away, depending upon the size of the charge that was set. Coehorn mortars were useful for lobbing explosive shells at a high angle, at low velocity, for short distances, which made them ideal for lobbing shells from one trench line to another.

Artillery Commander John Tidball, explained how the Coehorn mortar was transported and used:

The mortar is carried on the caisson body, the front chest being removed for this purpose. The piece is securely lashed with ropes through the handles. The remaining ammunition chests are arranged to carry thirty shells each. The powder is in cans, and a set of measures (from one to six ounces) should be provided. The shells should be charged and fuse-plugs driven, ready for the insertion of the fuses. Additional caissons carried more ammunition chests as needed.”

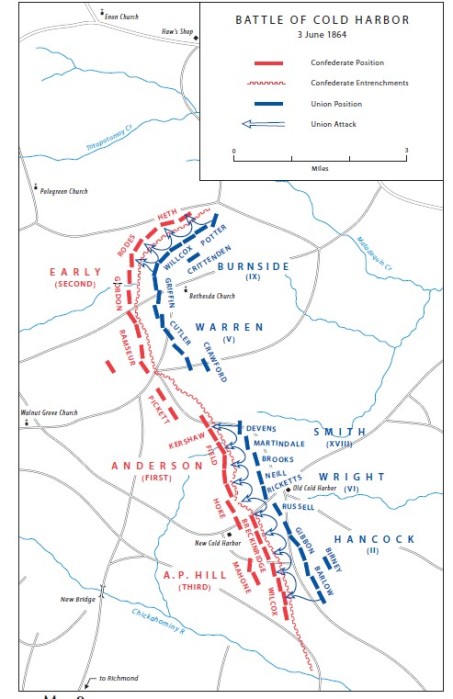

From this description, we see that the Coehorn mortar was kept loaded and ready for firing at short notice. On June 1, Company D was ordered to continue marching south with their regiment. Their Coehorn mortars were placed in wagons while they marched. They reached Cold Harbor where the Union Army was engaged in an offensive battle with Confederates to clear the route to Richmond. Cold Harbor was a vital location because all the roads to Richmond converged at that point. Arriving at the front of the lines, there was a sense of foreboding that led some Union soldiers to write their names and addresses on pieces of paper that they pinned to their backs so that their bodies could later be identified. The battle lines there were close, only a few hundred yards apart, so the soldiers had to dig a line of trenches and throw up breastworks to protect their artillery. They each dug pits where they spent the nights. They dug out the trenches and pits using shovels, axes, bayonets, spoons, and tin pans and cups. Artillery fired back and forth.

On June 4, Tom Dunham, a soldier with Company D, said he was “pretty tired from carrying mortars and ammunition nearly half mile.” With their regiment closest to enemy lines, sometimes within 50 yards, Company D fired their six Coehorns to discourage the deadly activity of enemy sharpshooters. Captain James H. Wood, mortar battery commander, reported:

The result was almost instantaneous. Their firing was suppressed and was not resumed for several hours… during the affair two rebels were seen to be blown 10 feet in the air… their companions wildly scattered in every direction.”

The bodies of fallen soldiers remained between the rebel and union lines since the battle at Cold Harbor began on June 3. The stench of hundreds of human bodies lying between the lines of the contending armies was almost unbearable. James Lockwood, a fellow-soldier of Barney’s in Company D, observed:

Charge after charge had been made for the purpose of dislodging the enemy by storm; and in every instance had resulted in a failure and also fearful loss in killed and wounded, the latter of whom were compelled to lie where they fell, upon the ground, under the fierce and burning rays of the sun, without water or food, and their slightest movements calling down upon them a malicious and pitiless storm of leaden hail from the rebels, until they were mercifully released by death.”

Since the dead and wounded were Union soldiers, the rebels kept refusing to call an armistice to allow for them to be removed until the wind changed direction and carried the stench of death toward the rebels. A truce was called for two hours on June 7 to allow for the bodies to be removed and buried. By then, all but two of the wounded soldiers had died.

When not burying the dead, digging trenches, building breastworks, marching, fighting, and sleeping in the pits he dug, what were Barney’s meals like? While the troops were marching from the North Anna River to Cold Harbor, General Grant moved his supply depot 70 miles south from Fredericksburg to White House Landing. In the meantime, the distribution of rations to the troops was interrupted. Many of the soldiers went without food for up to 48 hours. Like other soldiers, Barney might have spent $1 of his hard-earned $13-monthly pay to purchase a hard tack biscuit from those who had some. The soldiers who bought the hard tack must have been desperate, based on a description of hard tack in the memoirs of another Union soldier, John Billings:

What was hardtack? It was a plain flour-and-water biscuit. Two which I have in my possession as mementos measure three and one-eighth by two and seven-eighths inches, and are nearly half an inch thick. Although these biscuits were furnished to organizations by weight, they were dealt out to the men by number, nine constituting a ration in some regiments, and ten in others; but there were usually enough for those who wanted more, as some men would not draw them. While hardtack was nutritious, yet a hungry man could eat his ten in a short time and still be hungry. When they were poor and fit objects for the soldiers’ wrath, it was due to one of three conditions: first, they may have been so hard that they could not be bitten; it then required a very strong blow of the fist to break them; the second condition was when they were moldy or wet, as sometimes happened, and should not have been given to the soldiers: the third condition was when from storage they had become infested with maggots.

When the bread was moldy or moist, it was thrown away and made good at the next drawing, so that the men were not the losers; but in the case of its being infested with the weevils, they had to stand it as a rule ; but hardtack was not so bad an article of food, even when traversed by insects, as may be supposed. Eaten in the dark, no one could tell the difference between it and hardtack that was untenanted. It was no uncommon occurrence for a man to find the surface of his pot of coffee swimming with weevils, after breaking up hardtack in it, which had come out of the fragments only to drown; but they were easily skimmed off, and left no distinctive flavor behind.

Having gone so far, I know the reader will be interested to learn of the styles in which this particular article was served up by the soldiers. Of course, many of them were eaten just as they were received — hardtack plain; then I have already spoken of their being crumbed in coffee, giving the “hardtack and coffee.”

Probably more were eaten in this way than in any other, for they thus frequently furnished the soldier his breakfast and supper. But there were other and more appetizing ways of preparing them. Many of the soldiers, partly through a slight taste for the business but more from force of circumstances, became in their way and opinion experts in the art of cooking the greatest variety of dishes with the smallest amount of capital.

Some of these crumbed them in soups for want of other thickening. For this purpose they served very well. Some crumbed them in cold water, then fried the crumbs in the juice and fat of meat. A dish akin to this one which was said to make the hair curl, and certainly was indigestible enough to satisfy the cravings of the most ambitious dyspeptic, was prepared by soaking hardtack in cold water, then frying them brown in pork fat, salting to taste. Another name for this dish was skillygalee. Some liked them toasted, either to crumb in coffee, or if a sutler was at hand whom they could patronize, to butter. The toasting generally took place from the end of a split stick.

Then they worked into milk-toast made of condensed milk at seventy-five cents a can; but only a recruit with a big bounty, or an old vet, the child of wealthy parents, or a reenlisted man did much in that way. A few who succeeded by hook or by crook in saving up a portion of their sugar ration spread it upon hardtack. And so in various ways the ingenuity of the men was taxed to make this plainest and commonest, yet most serviceable of army food, to do duty in every conceivable combination.”

On June 8, extra rations were issued in addition to the hard tack and salt pork normally received. Soldiers feasted on dried apples, pickled cabbage, and potatoes. The fighting continued at Cold Harbor until General Grant realized his army was bogged down in trench warfare with the rebels and they were no closer to their Richmond destination. He changed tactics and decided to march his army to Petersburgh, crossing the James River on ferries and pontoons. General Grant said:

[Confederate General] Lee’s position was now so near Richmond, and the intervening swamps of the Chickahominy so great an obstacle to the movement of troops in the face of an enemy, that I determined to make my next left flank move carry the Army of the Potomac south of the James River.”

On June 12, Barney’s regiment left Cold Harbor and crossed the Richmond and York River Railroad and the Chickahominy at Lowbridge, and crossed the James River by ferry. The regiment loaded and unloaded the ammunition and other trains. Artillery Commander John Tidball recalled:

The labor of embarking and disembarking this immense train was performed under the most disadvantageous circumstances by the Fourth New York Artillery, who worked with a will and constancy creditable to both officers and men.”

Confederate General Lee had tried unsuccessfully to block their advance across the James River, accurately predicting the outcome:

We must destroy this army of Grant’s before he gets to [the] James River. If he gets there, it will become a siege, and then it will be a mere question of time.”

To be continued: Part 6 – Barney spends the winter near Petersburg

_____________________________________________________________

Sources:

Life and Adventures of a Drummer Boy, or Seven Years a Soldier, by James D. Lockwood, Published by John Skiner, Albany, New York, 1893.

Heavy guns and light: a history of the 4th New York Heavy Artillery, by Hyland C. Kirk, 1890, New York: C.T. Dillingham

The Diary of a Line Officer, by Captain Augustus C. Brown at Openlibrary.org, accessed Dec. 30, 2014

To the North Anna River: Grant And Lee, May 13-25, 1864, by Gordon C. Rhea, 2000, Louisiana State University Press: 2000

Trench Warfare Under Grant & Lee: Field Fortifications in the Overland Campaign, Earl J. Hess, accessed May 20, 2015 at books.google.com

The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Volume XL, Part 1 (Serial Number 80), pages 433-434

The Overland Campaign, by David Hogan Jr., Center of Military History, U.S. Army: Washington D.C.,, 2014, accessed August 2, 2015 at http://www.history.army.mil/html/books/075/75-12/cmhPub_75-12.pdf

Civil War Diary Of Thomas “Tom” Dunham, Age 21, Spring & Summer 1864, Company D, 4th Regiment, (New York Volunteers) Heavy Artillery, http://www.hamilton.nygenweb.net/military/dunhamdiary.html, accessed August 5, 2015.

Personal Memoirs of U. S. Grant, by Ulysses Grant, 1885 The American Civil War, accessed August 10, 2015 at http://www.civilwar-online.com/2015/01/january-21-1865-coehorn-mortar.html

Hardtack and Coffee or, The Unwritten Story of Army Life, by John D. Billings, 1898, George M. Smith and Company, Boston.